Brazil’s Environmental Policy: A Model for the United States?

In a 2009 study conducted by the Public Library of Science on the evaluation of the relative environmental impact of countries, Brazil ranked 1st on a scale measuring absolute composite environmental rank. The study’s methodology used a lower rank to correlate with a higher negative impact. Thus, Brazil had the highest overall negative impact on its environment of any country. According to this study:

- National Forest Lost Rank: 1st

- Natural Habitat Conversion Rank: 3rd

- Marine Captures Rank: 30th

- Fertilizer Use Rank: 3rd

- Water Pollution Rank: 8th

- Threatened Species Rank: 4th

- Carbon Emissions Rank: 4th

- Absolute Composite Environmental Rank = 4.5 (1st)

While these numbers appear bleak for the country that just hosted the World Cup and the Olympics in two years, Brazil, according to the Economist, has become the world leader in reducing environmental degradation in recent years.

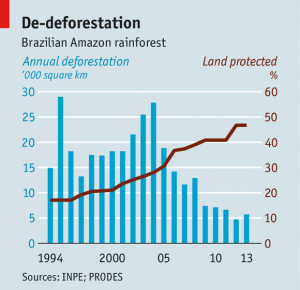

In the 1990s, Brazil felled rainforest the size of Belgium annually. However, in the past decade, Brazil has reduced deforestation by nearly 70 percent in the Amazonian jungle. If deforestation had continued at its 2005 rate of 19,500 km2 per year, an extra 3.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide would have been emitted. Thus, Brazil could also be viewed as a pioneer for climate change mitigation. Unlike other countries, such as Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil has been able to slow and stop these clearances. The reason for its success has been a result of incremental efforts in three stages.

- Stage 1 (mid-1990s – 2004): The Brazilian government implemented its first bans and restrictions, one of which stated that on every farm in the Amazon, 80 percent of the land had to be set aside as a forest reserve. However, this was the worst period of deforestation because the share was so high that farmers could not comply with the code.

- Stage 2 (2004 – 2009): The government, making deforestation a priority under president Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, banned farming in nearly half of the Amazon rainforest, as opposed to the original ban on only one-sixth of the area. Additionally, buyers of Brazil’s soybeans declared they would not purchase crops on land cleared after July 2006, discouraging deforestation.

- Stage 3 (2009 – present): The government banned farmers in the 36 counties with the worst deforestation rates from getting cheap credit until rates fell. Furthermore, a proper land registry, which required that farmers report their properties’ boundaries, was created.

Clearly, as the graph above reveals, Brazil has had great success over the last decade at protecting its forests and preventing deforestation. More amazing, even with these regulations to improve environmental degradation, Brazil has had a dramatic increase in food output. Thus, Brazil is proof that a country can achieve environmental and economic gains simultaneously. Although these government regulations would not likely succeed in the United States, perhaps Brazil serves as a model for the U.S. for its priority on environmental protection.

Although forest composes less percent area of the U.S. than it does in Brazil, protecting the infrastructure, creating more efficient energy resources, and improving resource management in the U.S. would serve useful for the economy and the environment. Additionally, as Brazil is proof, improving the environment does not necessarily mean hindering the economy. While regulating carbon emissions in the U.S. will likely cause more economic turmoil, using the bright green framework as the basis for future environmental policy may have success from both the economic and environment perspectives.

Tanner Davis is a research associate at the National Center for Policy Analysis.