The Atlanta Transit Tax: For the 1 Percent

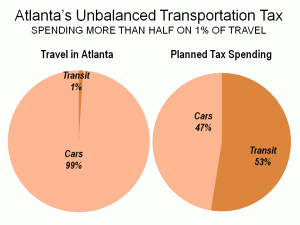

Voters in Atlanta, with some of the worst traffic congestion in the nation, are being asked to approve a new tax that would spend more than 50% on transit, in an urban area where transit carries only 1% of travel (Figure). No one is naive enough to think that the new billions for transit would improve traffic congestion. Worse, the distorted program would contribute to worse congestion by spending on billions on transit, which cannot reduce traffic congestion, instead of on roadways, which is the only way that traffic congestion can be reduced.

The July 31 vote is in 10 counties of the 28 county Atlanta metropolitan area. The measure would raise the sales tax by one cent, for $8 billion in transit and highway projects over 10 years.

In a metropolitan area in which barely one percent of travel is by transit, the tax measure would devote more than one-half of the funding to transit (see Figure). As we wrote in an Atlanta Journal-Constitution commentary, the focus of any transportation revenue issue should be on reducing travel times, whether by transit or highways. This is how transportation improves an urban economy. The reality is that with nearly all travel by highways and transit’s inherently slower travel times, much of the tax money would be spent on strategies that have virtually no hope of reducing travel times or traffic congestion.

Atlanta’s Traffic Congestion: Promoters of the tax claim that the highway projects will reduce traffic congestion. Atlanta is well known for its serious traffic congestion. There are two reasons for this:

(1) Atlanta has a sparse freeway system, which is limited to little more than a belt route (I-285) and three radial freeways (I-20, I-75 and I-85) that converge into two downtown. Seven years ago, we rated Atlanta as having the least effective freeway system among major US urban areas. Nothing has happened to change that rating, except for the addition of 750,000 people. This tax issue will do virtually nothing to improve roadway travel on the regional level.

(2) Perhaps even worse, Atlanta’s regional arterial (high capacity streets) system is virtually non-existent. For this reason, we proposed (in 2000) development of a one-mile terrain constrained grid of arterials . A local editorial writer found this so hard to deal with it that he misrepresented it as a mile grid of freeways to make it look extreme. Later, the Atlanta Regional Council (ARC), the local metropolitan planning organization, included a somewhat more modest (but useful) arterial grid in is regional plan.

The Transit Tax: Fixing What Should have Already Been Fixed: The transit projects have virtually no potential to reduce work trip travel times and thus no potential to reduce traffic congestion. Approximately one-fifth of the transit funding would be used to rehabilitate and upgrade the MARTA subway system, a need that should have been legitimately funded from the existing MARTA sales tax.

The Transit Tax: Subsidizing Land Speculation: Another nearly 20 percent of the transit funding would be spent on the “Belt-Line” streetcar project in central Atlanta. The Belt-Line is more “city building” (read “real estate speculating”) than it is transportation. It will do nothing to reduce work trip travel times. Further, it is exceedingly costly. The extravagance of this project is illustrated by an annualized capital cost alone (principally construction) high enough to pay the lease on a new mid-sized car for each new regular passenger.

The Transit Tax: Emulating Miami? The history of transit is fraught with cost increases and project cancellation and delay as transit agencies, unable to control their rising costs, can spend money for day-to-day operations that had been planned to build new transit lines. This has happened with a vengeance in Miami, where a 2002 transit tax to expand the rail system has largely been frittered away in higher operating costs. It could happen in Atlanta.

The Road Projects: In a metropolitan area in which personal mobility predominates, roadway improvements, such as expansions, an arterial grid in Atlanta’s case and completion of the GA-DOT HOT (high occupancy toll) system provide the greatest potential for reducing travel times. There is another significant benefit to highway investments. As traffic speeds increase fuel efficiency improves and both air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions are reduced.

With less than 50 percent of the funding going to roads, less than one-half the potential benefit of the $8 billion can be achieved. This ineffective return is felt by low income citizens almost to the same extent as everyone else. While 88 percent of all commuters in Atlanta travel by car, the figure is only slightly less (83 percent) among low income commuters (Figure 4).

What’s Right About Atlanta: For all its problems, Atlanta has much to be proud of. Former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud said of Atlanta in a 2002 study:

While income and population were rising very fast, Atlanta managed to keep a very low cost of living. A worldwide cost of living survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2002 found that Atlanta had the lowest cost of living among major US cities and ranked 63rdamong major cities around the world. This achievement is remarkable in view of the rapid rate of growth of the metropolitan area over the last 20 years. It shows that while demographic and economic growth has certainly contributed to generate pollution and congestion, the various actors responsible for the management of metropolitan Atlanta must have done a lot of things right. High income growth and high demographic growth combined with a low cost of living suggests that labor markets are functioning well and that housing does not encounter important supply bottlenecks. (Note on Atlanta’s Superior Housing Affordabilitiy)

Atlanta’s leadership should go back to the drawing board. A rational proposal is required to reduce Atlanta’s travel times (which are longer than its major US competitors, such as Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston) and grow the economy. There’s no point in spending more than 50 percent on the 1 percent.

(More at The Atlanta Transportation Tax: Too Much for Too Little.)

——

Note on Atlanta’s Superior Housing Affordability: Atlanta was most affordable major metropolitan area in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and Hong Kong in the 8th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey.

Well stated, so well in fact, that the problem description also reveals the solution.

Simply break the funding into separate projects and let the voters vote on them as follows:

Highways

Transit

Land speculation

The ones that are approved go forward and the ones that fail do not.

Gas taxes are for the roads. If it is not enough to cover the costs then they should double, quintuple, or whatever it takes to cover it. Wendell Cox already wrote an article stating that roads pay for themselves so why is he now saying that a percentage of this sales tax should go to roads? It is obvious that contradiction signifies he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.