Sniffing Out Bad Environmental Policies Is Much Like Culling Rotten Produce

When buying produce, we’ve found ways to discern which pieces are worthy to place in our basket. Each piece of fruit or stalk of vegetable must be of good quality to justify spending our hard-earned income on it. So we look, we sniff and we gently squeeze them in order to cull the unripe or rotten pieces and glean the good ones.

Perhaps we should use a similar approach when evaluating the competing environmental proposals proffered by various organizations. We should carefully sniff out the rotten assumptions and gently squeeze the reasoning of their justifications in order to glean which proposals might be worthy of our real sacrifice in national treasure and personal freedoms.

For example, consider the World Bank’s proposals for reducing man-made influences over global climate change. Like most other organizations, they stress the urgency for all nations to take immediate, coordinated actions to reduce carbon emissions. However, they stress that the needed sacrifices should not be shared equally among the nations.

Upon closer inspection, the World Bank’s policy recommendations reveal intellectually unripe assumptions that employ ethically rotten reasoning to justify them. For example, in the World Development Report 2010, the President of the World Bank stresses that,

Developed countries have produced most of the emissions of the past and have higher per-capita emissions. These countries should lead the way by significantly reducing their carbon footprints and stimulating research into green alternatives.

First, consider the intellectually unripe assumption that per-capita carbon emissions are an appropriate basis for determining relative global warming culpability across the nations, and to identify which nations should bear the brunt of costly remediation efforts.

Let’s remember that carbon emissions result from economic activity. All else equal, greater economic activity in a nation’s economy creates greater carbon emissions per capita, but also greater prosperity (output per capita) for its citizens enjoy.

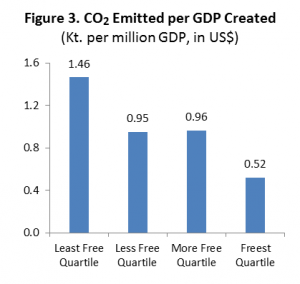

Humanitarians should want the citizens of all nations to become prosperous, but to achieve their prosperity with the smallest environmental footprint possible. Therefore, would not an intellectually ripe indicator of culpability be carbon emissions per-dollar of economic output?

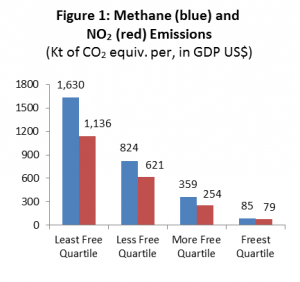

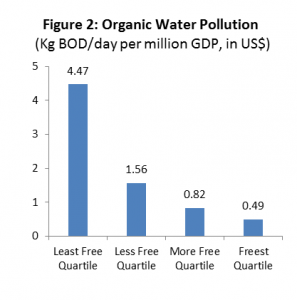

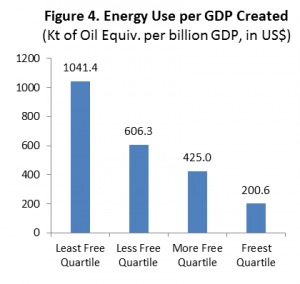

Using this perspective, we could identify the various institutional characteristics among the nations that tend to create a “greener” prosperity, which would then better inform the efforts of environmental policy makers. For example, I point out in an earlier blog post that countries pursuing prosperity through free markets rather than through centralized planning consistently produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions, per dollar of GDP.

Second, consider the ethically rotten policy implications that this intellectually unripe measure would likely create: In order for a nation with heavy carbon emissions per capita to reduce its culpability in global warming crimes against humanity, it must make relatively greater sacrifices. It must decrease its economic activity using current technologies and divert significant portions of its national treasure towards developing “green” technologies. Nations with lower per-capita emissions would not be called upon to sacrifice as much.

This means a country like China, which has an economy similar in size to the U.S. but generates 43% more total carbon emissions, would be expected to sacrifice less than the U.S. Why? With its 2 billion citizens (6 times the 325 million U.S. citizens), Chinese carbon emissions per capita are still far lower than the U.S.

This ethically rotten perspective ignores the fact that China has produced far more carbon emissions per dollar GDP than the U.S. As a result, Chinese citizens bear a much lower level of prosperity (output per person) than U.S. citizens, despite having imposed a far larger total environmental footprint than the U.S.

Using per-capita carbon emissions as an indicator of climate change culpability? Hmm… I think I smell something rotten in Denmark.