“Call us for more information and to see if you qualify!”

What exciting opportunity might this be? How about the chance to be exposed to toxins that the researchers say can cause death.

Indeed, this cheery offer came from a set of flyers printed by the EPA seeking human testing subjects for air pollution experiments.

According to an EPA Inspector General report, during five studies conducted in 2010 and 2011, the EPA conducted experiments on 81 individuals, exposing them to airborne particles known as PM2.5 (basically, soot and dust), diesel exhaust, and ozone. Some test subjects experienced cardiac arrhythmias during the testing, and one woman, with a history of medical problems, was sent to the hospital.

The report describes the five air quality studies, expressing concern that the agency exposed a research subject above the study’s concentration targets and that the EPA’s consent forms did not address all of the risks (including death) surrounding pollutant exposure.

Moreover, only one of the studies’ consent forms “identified the upper range of pollutant exposure for each study subject.” The other four consent forms “did not mention the level of pollutant exposure. Instead, the forms…compared the subject’s level of exposure during the study to the exposure they would receive visiting major cities on smoggy days.”

Why was this info left out? The EPA justified its “smoggy days” description of the study because a study manager “explained that a person breathing 420 [micrograms per cubic meter] for 2 hours would inhale the same concentration as they would breathing 35 [micrograms per cubic meter] (the EPA’s 24-hour standard for PM2.5) for 24 hours in a city such as Los Angeles.”

(The studies actually exposed participants to PM levels of 600 micrograms per cubic meter, and one subject up to 751 micrograms per cubic meter — over 21 times the 24-hour standard!)

“The manager also stated that…the risk is small for those with no overt disease.”

Similarly, the agency failed to mention long-term cancer risks from diesel exhaust because “[a]n EPA manager considered these long-term risks minimal for short-term study exposures.”

And just two of the studies “alerted study subjects to the risk of death for older individuals with cardiovascular disease.”

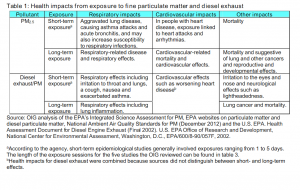

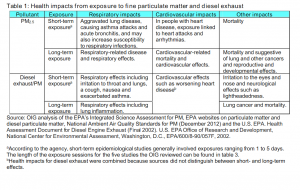

The IG report provides a table detailing health impacts derived from EPA regulations and assessments from short-term exposure to particulate matter and diesel exhaust. For PM2.5, “mortality” is listed as a risk of short-term exposure.

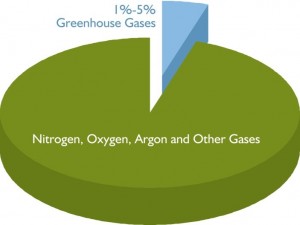

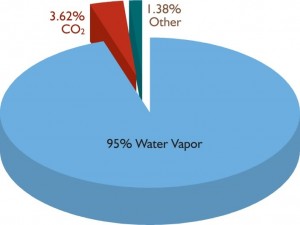

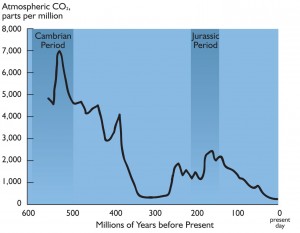

What else has the EPA told us about PM2.5?

- “If we could reduce particulate matter to levels that are healthy, we would have an identical impact to finding a cure for cancer.” — EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson, testimony in front of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, September 22, 2011.

- “Particulate matter causes premature deaths. It doesn’t make you sick. It is directly causal to dying sooner than you should.” — EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson, testimony in front of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, House Committee on Energy and Commerce, September 22, 2011.

- “Overall, there is strong epidemiological evidence linking… short-term (hours, days) exposures to PM2.5 with cardiovascular and respiratory mortality and morbidity.” — EPA report on Air Quality Criteria for Particulate Matter, Volume II, October 2004.

- “Short-term exposures to particles (hours or days) can aggravate lung disease, causing asthma attacks and acute bronchitis, and may also increase susceptibility to respiratory infections. In people with heart disease, short-term exposures have been linked to heart attacks and arrhythmias.” — EPA brochure on Particle Pollution and Your Health.

- “The new studies support previous conclusions that short-term exposure to fine PM is associated with both mortality and morbidity.” — EPA report on Provisional Assessment of Recent Studies on Health Effects of Particulate Matter Exposure, July 2006.

- “The best scientific evidence, confirmed by independent, Congressionally-mandated expert panels, is that there is no threshold level of fine particle pollution below which health risk reductions are not achieved by reduced exposure.” — Letter from Gina McCarthy, Asst. Administrator of the EPA, to Rep. Fred Upton, February 3, 2012.

In these reports and statements, exposure to PM 2.5 is dangerous (indeed, there is apparently no level of pollution at which health risks cease!). But the EPA’s human testing? Apparently not so dangerous.

The IG report summed up the agency’s missing warnings about the link between PM exposure and health effects this way: “This lack of warning about PM…is also different from its public message about PM.”

When an agency hails the reduction of particulate matter as the public health equivalent of curing cancer — and regulates on that basis — it loses credibility when it exposes humans to high levels of the pollutants and deems such exposure safe.

So, has the EPA exaggerated the effects of these particles in order to justify heavy-handed regulation? Or is the agency knowingly conducting dangerous experiments on human subjects?

Whichever it is, neither answer is comforting.