Los Angeles County Supervisor Mark Ridley – Thomas talks glowingly of rail transit in Los Angeles in a recent Honolulu Star-Advertiser commentary. However, nowhere did he say that rail transit had reduced traffic congestion or increased transit ridership. There is a good reason for this — it did not happen.

It is useful to consider the Los Angeles rail experience in comparison with the promises and expectations that existed when it was created. I was present at the creation and played a major role in the establishment of the Los Angeles rail system.

Supervisor Ridley-Thomas represents the second district in Los Angeles County, which at one time was represented by Kenneth Hahn, a legendary fixture in Los Angeles governance for nearly 50 years. I had the pleasure of serving on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (LACTC) along with Supervisor Hahn, who I considered a good friend. LACTC was the top transportation policy authority in the nation’s largest county. I was appointed by Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley to three terms on LACTC, whose membership also included the five county supervisors, the Mayor of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles City Council President, the Mayor of Long Beach and two elected officials from smaller cities. I was the only private citizen on the LACTC, which was a predecessor of the Los Angeles MTA, the body on which Supervisor Ridley – Thomas serves.

I had become involved in transportation issues because of my belief that building a rail system in Los Angeles would reduce its intense traffic congestion. In August of 1980, Supervisor (and LACTC chair) Hahn called a special meeting to consider his proposal for reduced fare program to be financed by a countywide sales tax, which LACTC would place on the ballot under its legislative authority. Fearing the loss of the most important opportunity to bring rapid transit to Los Angeles, I took the initiative to confer with Supervisor Baxter Ward, a strong rail supporter, who agreed to second a motion to dedicate 35% of the funds to rail after a three year reduced fare period (Supervisor Ward’s amendment to set-aside a larger share had been previously defeated). My motion passed, and was incorporated into the “Proposition A” ballot issue, which provided nearly all the funding for the first light rail line and substantial amounts of funding for four additional lines. My motion was the genesis of the Los Angeles rail system.

Meanwhile, two subsequent taxes were approved by voters to provide funding for urban rail, since the escalating costs of the rail system rendered the Proposition A sales tax insufficient to keep the promises made by LACTC. At the beginning of 2011, five rail lines radiated from the urban core, with a sixth (cross-town) line in the inner suburbs.

It is well to step back and review the results. Many self-proclaimed transit advocates (more are actually advocates of transit funding, with little concern about generating more transit ridership) seem to mere require the running of shiny trains to prove the success of rail. In fact, rail can be justified only by the extent to which it cost effectively reduces traffic congestion and increases transit ridership. Based upon those practical standards, any objective analysis of rail transit in Los Angeles has to conclude that it has been an extravagant failure.

The hoped-for traffic congestion reduction did not occur. Not only that, transit ridership did not increase. Today, there are 7 percent fewer riders on the MTA bus and rail services then there were on buses alone in 1985. By contrast, over the period, the population of Los Angeles County grew by approximately 20 percent.

But while MTA ridership was falling, costs increased substantially. The latest National Transit Database information (2010) indicates that MTA’s daily operating costs have increased nearly one third since 1985, after adjustment for inflation. This is before considering the approximately $12 billion (in 2011$) of local, state and federal tax funding used to build the rail lines. Thus, now spending $300 million more annually and approximately $12 billion in construction and related expenses, transit ridership remains below the 1985 level. Los Angeles and the nation’s taxpayers have spent that much money and the effect is not even to “tread water” in transit ridership.

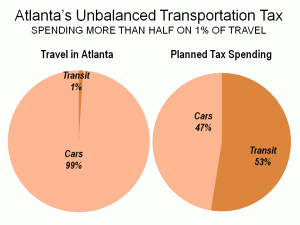

The number of daily work trip commuters carried on the MTA light rail and subway system is miniscule. The US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data indicates that in 2011, approximately 20,000 daily one-way commuters used MTA’s six rail lines to get to work, little more than one-half of one percent of work trip commuting in Los Angeles County (3.6 million use cars daily to get to work).

At the same time, traffic volumes have increased substantially and travel speeds have declined. Since the first rail line opened in 1990, the average one-way work trip in Los Angeles County has increased nearly 3 minutes, from 26.5 minutes to 29.4 minutes in 2011.

By comparison, there has been a more than 100,000 increase in the number of people working at home (mostly telecommuting) since 1990 — five times the number of people commuting by rail. This increase in working at home has required virtually no tax funding, a stark contrast to the cost of rail.

The Los Angeles rail experience illustrates a fundamental difficulty in US and even international urban infrastructure policy. Too often, proponents confuse means and ends (objectives). Analysts often judge urban areas based upon issues such as the extent of rail transit systems. Yet, rail transit systems (and highways) are means, not objectives. Urban policy needs to focus on objectives. The purpose of urban areas is economic. People move to cities to improve their standard of living, not to ride trains, admire fountains or experience “good” urban planning. Perhaps the most important measure of an urban area’s performance is the amount of income households have left over after for the necessities of life, such as housing, food and, of course, taxes. Infrastructure is a means, but not the objective. It should be selected for its contribution to the objective of improving the standard of living of the urban area’s households.

—-

Note: This article is adapted from a column in the Hawaii Reporter.