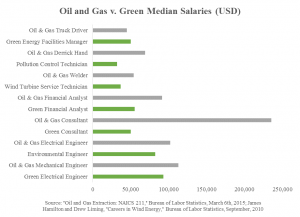

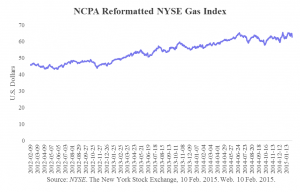

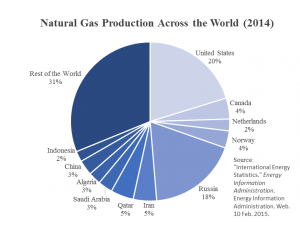

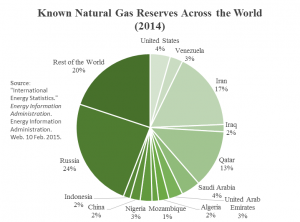

Hydraulic fracturing or “fracking” is a well completion technique that is the key to America’s shale boom. Because of hydraulic fracturing, the U.S. has become the world’s top natural gas producer and has gained the capability to become the world’s top oil producer. The shale boom has generated a great majority of jobs created since the recession, and created great wealth for the states where shale deposits are found.

Despite the benefits of energy production, hydraulic fracturing bans and draconian regulations have become more and more common at both the state and local level. To date, greater than 400 municipalities around the country have passed frac restrictions according to Food and Water Watch, an environmental group that tracks anti-fracturing activism. The trend appears to be increasing nationally.

The significance of local bans is little discussed in the energy sector, and underreported, at least from a macro perspective. While the press widely reported that the state of New York passed a statewide moratorium on hydraulic fracturing, few noted that the State was already home to greater than 200 municipal bans on fracking before the state imposed a statewide restriction. Restated, greater than 200 New York communities debated the question of whether to permit hydraulic fracturing and concluded that restricting production and wealth generation was the best policy.

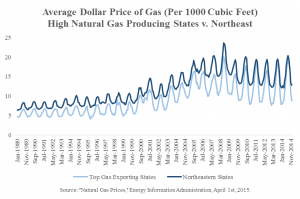

Some industry observer dismiss frac bans as inconsequential because they often pass in areas that have little or no frac activity anyway, such as in the case of the statewide ban in Vermont. “The market will adjust,” is the common mantra among producers. One should note, however, that frac restrictions are concentrated on the West and East coasts, where many of the nation’s rich shale deposits lie, such as the Marcellus (NY) and Monterey (CA). Likewise, the public opinion that is formed in the cities and towns will likely factor into future action at the state level, as we have seen in New York and as we are likely to see in California and Colorado.

Can energy producers rely on the states to override local bans to protect their activity? In Texas, probably yes. In California and Colorado, it is much less certain. If public opinion can be our guide, the outlook is not so good. Countrywide, in November of 2014, only 41% of Americans polled favored the increased use of fracking while 47% were opposed. By contrast less, just one year before, there was more support (48%) than opposition (38%) to the drilling technique. Some surmise that the unpopularity of fracking is limited to the coasts, but the Pew poll of 2014 shows that the most dramatic shift in opinion is seen in the Midwest where support for hydraulic fracturing dropped a breathtaking 16 points from 55% to 39% from 2013 to 2014.

San Benito County, California — one of over twenty localities which have banned fracking activity in the state — is currently locked in a legal battle with Citadel Exploration, an energy company which claims that only the state of California itself (as opposed to municipalities) has the ability to ban fracking. Even if Citadel Exploration prevails, should proponents of fracking feel that California production investments are safe? Barely a year ago, the Californian state Senate nearly enacted a moratorium to ban fracking temporarily. With a final count of 18-16 against the ban, the state only lacked two votes for a majority pass. The same trend has been seen in other states, like New York and New Jersey where the temporary period of inactivity in the gas sector is followed by more outcries from environmentalist groups, and the subsequent drafting of more final, permanent restrictions on hydraulic fracturing.

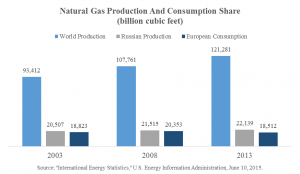

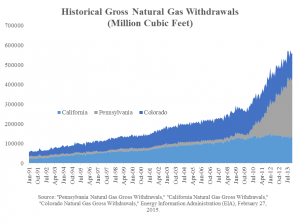

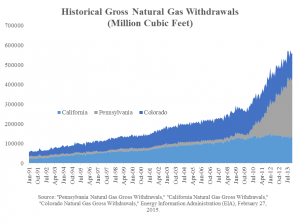

The cost of these bans is high, especially given the sheer quantity of untapped or undiscovered natural resources. California, Pennsylvania and Colorado are three possible battlegrounds to watch in the future, all of which contain high concentrations of gas resources and formidable past opposition either in their local communities or their state legislatures. The cost of completely eliminating the production of these resources is outlined by the sheer quantity they withdraw for sale on a monthly basis. Based on the graph below, at an average cost of $2.69 per million cubic feet (mcf), the states of CA, PA, and CO would lose almost $1,611,300 in monthly production revenue for natural gas alone, without even considering oil.

The list of counties which have banned fracking is growing on a monthly basis. In addition to state regulations, local government hydraulic fracturing restrictions now number in the hundreds, and are concentrated in CA and along the Eastern Seaboard. Policymakers must adopt an emphasis on balancing socially responsible results with protecting the rights and revenue generating capacities of the industry to insure continued job creation and economic growth.